ANDY WARHOL’S ALTERED EGO

.png)

In the months before and during the time the Altered Images shoot was taking place, Warhol’s personal and professional life was a mass of contradictions. He had enrolled with the modelling agencies Zoli and Ford and yet was fretting about his skin (something that had concerned him since his teens) and had been visiting the beautician Janet Sartin on a regular basis. He was considering plastic surgery and was routinely working out with a personal trainer; his weight having dropped to a very thin 118lbs, which he declared ‘he liked’. Warhol was also attempting to sustain a troubled and largely unrequited relationship with Jon Gould of Paramount Pictures but he surmised that that root of his ‘problems’ were because he was feeling old in comparison to the people he was surrounding himself with ‘all the young kids just budding’. It is against this emotionally turbulent background that the Altered Images sessions take place.

Warhol’s fascination with Divas and the world of Hollywood glamour stemmed from a childhood growing up in industrial Pittsburgh where he collected autographed prints of the Hollywood movie stars including Mae West, Marilyn Monroe and Shirley Temple. He loved Greta Garbo’s pencilled brow and Joan Crawford’s extended false lashes and was fascinated by the transformation of Norma Jean. He knew that Hollywood stars were enhanced in the 1940s and 1950s with copious makeup, specialist lighting, hair dyes, hairpieces and extensive retouching. His collection of magazines including Movie Mirror, Screen Stars and Photoplay had artwork portraits of the stars on their covers (similar to Warhol’s Interview magazine) and would reveal star ‘secrets’. Warhol’s drawings of Eyelashes (1950s) and Lips (1950s) illustrations for women’s makeup and Cosmetics (1962) highlighted his interest in products and their ability to alter shape and draw attention to facial features. This is further emphasised in his drawn copy of a Maybelline advert entitled Hedy Lamar (1962) inscribed ‘To Maybelline the eye make up I find so totally flattering’. In another Hollywood example Female Movie Star (composite) (1962) he combines Greta Garbo’s eyes with Sophia Loren’s lips. The bathroom cabinet in his New York town house was overflowing with beauty products for disguising spots, dying his wigs and bleaching his eyebrows which by 1981 were bushy and snow white and it is no accident that the video of the portrait session includes a close up shot of the makeup, brushes and sponges being used. He had by 1981 taken polaroid shots of numerous stars including Liz Taylor and Jane Fonda (the latter bringing her own make up artist to the session) in preparation for portraits, noting their hair and red lips and had seen close up their faces, makeup and flaws. His concern for his own skin is highlighted as he observes the amount of pan makeup being applied in the photo shoot and frets “Do you think my skin isn’t breathing, she (Sarin) told me not to put anything on it” and “go gently on my face”. He sees a pimple and says dramatically “blood poisoning”. It is then Warhol’s cumulative artistic sensibilities and obsessive concerns which appear to resonate in the Altered Images photographs and Drag and Transformation Video.

His pursuit of the beautiful is played against his dissatisfaction with his own looks which was endemic. In true Diva style, Warhol had surrounded himself with an entourage which by the 1980s consisted of a ‘business enterprise’ with each member including Christopher Makos and Bob Colacello (who can be heard off camera in the video) having a specific role and function. Makos worked on Warhol’s Interview magazine for the column IN and often accompanied him on trips taking numerous ‘casual’ portraits of him. Impressed with Makos’s White Trash (1977) and quipping that he was ‘the most modern photographer in America’ Warhol used him as Art Director on his book Andy Warhol Exposures as well employing him to print up his photographic images. “One thing I have learnt from Chris if you tell anybody to do anything they do it…he’s pushy but then he’s not pushy”.

That the Altered Images shoot was a collaboration between Warhol and Makos is not in dispute, but there is an interesting dynamic between the filmed transformation and the stilled images and a distinct difference between the two photographic sessions in 1981. The doubling up of video, polaroid and Makos’ images were part of Warhol’s philosophy of ‘the more the better’ that it was best to take up as much ‘space’ as possible by putting work ‘out there’ in as many media as you can.

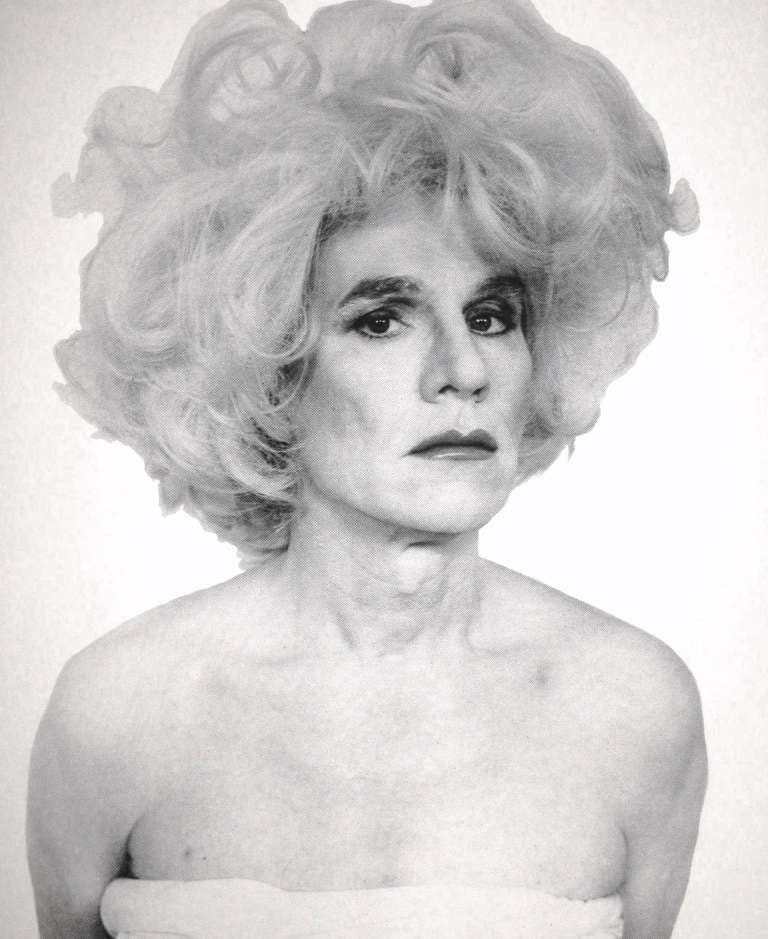

The transformation that is enacted and recorded in Altered Images is not about drag Makos explains but ‘altering’ an important distinction. The decision not to use the sequined dress that designer Halston (Warhol’s close friend) had offered was pertinent, this is about Andy Warhol as Alter Ego and it was essential to evoke a frisson of ambiguity, with Warhol retaining a clear vision throughout the sessions of how he wanted to look. Although Man Ray’s photograph of Duchamp as his Alter Ego Rrose Sélavy (1921) has been cited as an influence it was not discussed during the session but was rather an academic and artistic starting point of reference. The ‘dressing up’ of Duchamp and Man Ray, the concept of the Alter Ego and photographic collaboration all appealed to him. Warhol collected Man Ray photographs and Makos had met Man Ray and been instructed in his studio. Rrose Selavy was the art historical gravitas, it was as Makos reiterates “something that we discussed, we wanted some artistic provenance, we did not want to do a copy, if there are some of the same poses it’s a coincidence” The choice of black and white was also important Makos could have more control over the developing and printing and they were considered more ‘Arty’.

The transformation that is enacted and recorded in Altered Images is not about drag Makos explains but ‘altering’ an important distinction. The decision not to use the sequined dress that designer Halston (Warhol’s close friend) had offered was pertinent, this is about Andy Warhol as Alter Ego and it was essential to evoke a frisson of ambiguity, with Warhol retaining a clear vision throughout the sessions of how he wanted to look. Although Man Ray’s photograph of Duchamp as his Alter Ego Rrose Sélavy (1921) has been cited as an influence it was not discussed during the session but was rather an academic and artistic starting point of reference. The ‘dressing up’ of Duchamp and Man Ray, the concept of the Alter Ego and photographic collaboration all appealed to him. Warhol collected Man Ray photographs and Makos had met Man Ray and been instructed in his studio. Rrose Selavy was the art historical gravitas, it was as Makos reiterates “something that we discussed, we wanted some artistic provenance, we did not want to do a copy, if there are some of the same poses it’s a coincidence” The choice of black and white was also important Makos could have more control over the developing and printing and they were considered more ‘Arty’.

The real time reveal in Drag and Transformation gradually unfolds with Warhol exclaiming during the extensive makeup session “it must be hard being a girl or a drag queen”; he understood the trials of “putting your face on” and sometimes railed against the fact that he was engaged in the “same old act”. He was aware that he was in danger of becoming a caricature of himself both in his one-line sound bite responses and his look. Having already had one ‘sitting’ he knows what he wants to achieve and directs John Matthews (the make up artist) with comments as he examines his face in the mirror. “Keep the look just natural” or “a little liner there… just a thin line” or “not too much eye shadow”. He is also curious about Matthews “Do you ever wear makeup?” he asks, the response ‘occasionally’ is all he needs to hear. In a doubling of constructed identity the wigs (there were a variety of these purchased for the two sessions both long and short, dark and blond and eight in total) are placed on top of Warhol’s own hair piece which was fashioned into an ‘almost crew-cut’. In a typical Warholian exaggeration about his wig he claims that he “cuts it every day” .

Cross-dressing gender identity and sexual ambiguity were loaded issues for Warhol who was painfully aware of people’s prejudice. As Makos has reiterated this is about Warhol’s face. “It was important not to alter the body to support visually the ambiguity…it had nothing to do with transexuality…There were hand gestures but the power is in the gaze and its not related to drag queens or drag aesthetic”. Warhol however records a note of anxiety in his diary about the images . ‘Christopher is having his photo show out in California and its going to highlight his photographs of me in drag, so just when we finally get Mrs. Regan this is going to be publicized. Time and Newsweek will probably pick it up and my reputation will be ruined’.

Cross-dressing gender identity and sexual ambiguity were loaded issues for Warhol who was painfully aware of people’s prejudice. As Makos has reiterated this is about Warhol’s face. “It was important not to alter the body to support visually the ambiguity…it had nothing to do with transexuality…There were hand gestures but the power is in the gaze and its not related to drag queens or drag aesthetic”. Warhol however records a note of anxiety in his diary about the images . ‘Christopher is having his photo show out in California and its going to highlight his photographs of me in drag, so just when we finally get Mrs. Regan this is going to be publicized. Time and Newsweek will probably pick it up and my reputation will be ruined’.

The session includes three different approaches to portraiture, the Polaroid shots, Makos’s black and white portraits and the behind the scenes video. The video camera travels up and down Warhol’s paint spattered jeans and reveals each stage of the process including the reflector and umbrellas used by Makos, a glass of wine and the fingerprints on the handheld mirror. It also records Rupert Smith at Warhol’s behest using his Polaroid camera silently taking a series of shots at various stages until told “that’s enough”. He does not direct Warhol who assumes a number of poses commenting “that’s good” as he is shown the result. Makos recalls that he didn’t see these shots “he didn’t show them around I was only aware of them after Warhol died” . Makos’ technique in contrast is proactive; he enthusiastically encourages and directs Warhol who is at ease with the flamboyant photographer. Variously told to ‘relax his face’, or ‘move his head’ and constantly cajoled with “that’s good”, “stay like that”, “OK that’s nice, that’s beautiful”, “you look great, you look good”, “that’s excellent real terrific”, “that’s pretty”, he reinforces the aesthetic of the shoot. Stepping away from Warhol he reminds him, “I want to get the whole look where you do something really elegant with your hands”. The image Andy Warhol (1982) is the final transformation as Warhol gazes out at us provocatively as an ambiguous and powerful beauty. The content of the work is not ‘this is who I am’ but this is ‘what I can look like’. As Warhol had remarked in Popism “Something extremely interesting was happening in men’s fashions too …this signaled big social changes that went beyond fashion into the question of sex roles.” Finally after three different looks including the addition of a tie which Warhol insisted on as ‘looking better’, he almost droops in front of the cameras gaze like a deconstructed Louis X1V without the costume.

Makos comments that Warhol never had a great self image he was a not a particular handsome man he was getting older… and I thought I gave him a terrific self image it is all about the notion of “who am I” and I think we were successful in confusion or simulation in a different way. In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol Warhol declares ‘ “I always hear myself saying “She’s a beauty!” or “He’s a beauty!” …But I honestly don’t know what beauty is”. Yet somehow Warhol in his jeans and tie with his hands on his hips captured and stilled is an improbable flawed and poignant beauty as we hear his touching request to “just change the look of my face, that’s all I want”.

“Oh God it’s real, it’s a pimple.” Andy Warhol Drag and Transformation 1981

Andy Warhol was complex and enigmatic despite his claims to the contrary. His art, lifestyle, distinctive wig, humble beginnings in Pittsburgh and ‘superstardom’ were a calculated combination of media manipulation, determination and talent. His intricate self-fashioning is subtly revealed in the Warhol and the Diva exhibition at The Lowry. The Factory Diary Andy in Drag (October 1981), Christopher Makos’ Altered Images series (1981-2) and the Self Portrait in Drag polaroids shot on two separate days in 1981 offer telling insights into Warhol’s desires, sensibilities and work ethic. His expressions and postures as he ‘gets into role’ are captured as his heavily made up face is transformed from a pale middle-aged man to female ‘Diva’.

No comments:

Post a Comment